Titanic survivor’s story told at Pigeon Forge museum

The first time I met Marshall Drew, he pulled out a well-worn book. “This,” he said with a chuckle, “is an announcement of my death.”

Of course, the published account of his demise was wrong. In fact, Marshall lived almost three quarters of a century longer.

But many of the passengers he was traveling with on that long-ago trip were not so fortunate.

Marshall was one of the survivors of the sinking of the Titanic. I had interviewed him years ago in Massachusetts. Now I was seeing his name listed on the passenger memorial for the Titanic Museum in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.

Since opening in 2010, the Titanic Museum has quickly become a popular Pigeon Forge attraction. The museum is a half-scale, permanent, three-deck re-creation of the Titanic, right down to the huge “iceberg” outside the ship.

All the priceless artifacts displayed in the museum were either carried from the ship and into lifeboats by passengers and crew or were found afloat soon after the sinking and quickly salvaged by rescue boats.

Upon entry, each guest receives a boarding pass bearing the name of an actual Titanic passenger or crewmember whose fate is revealed on the Memorial Wall at tour’s end. The Titanic had 2,224 passengers and crew aboard. Only 706 survived.

Marshall Drew’s story

To travel on the mighty Titanic was a big adventure for an 8-year-old boy, Marshall said when I interviewed him. Accompanied by his aunt and uncle, the child was on his way back home to America. He had lived with his aunt and uncle since the death of his mother when Marshall was two weeks old.

It was the Titanic’s maiden voyage and the luxury ship had been widely billed as unsinkable. Capt. E. J. Smith and his White Star Line employers had been hoping to win the blue ribbon awarded to the fastest ship afloat. Therefore, as historians have since noted, some of the usual safety precautions were disregarded.

Marshall remembered that the evening of the sinking a sumptuous dinner had been served and that he had sat in the foyer to watch some of the great people in all their finery.

Some of the richest people in the world were aboard the Titanic and some went down with her — Col. John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, Mr. and Mrs. Rothschild, Isadore Strauss and his wife Ida, who refused to leave him for the safety of a boat.

At 11:40 p.m. on Sunday, the 14th of April 1912, Marshall was in a bunk in the stateroom he shared with his aunt and uncle.

“I remember a jar and the sensation of motion,” Marshall recalled. The jolt was caused when the Titanic hit an iceberg ripping a 300-foot hole in her hull below the waterline.

“A steward knocked on our door to tell us to get dressed and come up to the boat deck,” he continued.

As Marshall walked topside with his aunt and uncle, he recalled that “it was very cold and the water was calm like a millpond. The sky was black and the water was black so that you couldn’t see any difference between them — it was totally black.”

To cries of “Women and children first,” Marshall and his aunt were put into Lifeboat 11, “the only lifeboat out of all 16 which was filled.”

“My aunt said good-bye to my uncle. She never saw him again.”

Sinking of the Titanic

Although reports have varied, Marshall said he “distinctly remembered” hearing the band playing as the lifeboats were rowed away. “The band was all lost.”

The only time he was scared, Marshall said, was when the lifeboat was lowered down the side of the liner. “They were supposed to have a lifeboat drill that Sunday but didn’t and the ropes on the davits didn’t work,” he said.

“The lifeboat went down by a series of jerks. First the bow would be up in the air, then the stern would be. I was afraid we were going to be dumped into the sea.”

Marshall recalled hearing an explosion before the Titanic sank. “The engines broke loose and fell through the hull. The forward funnel fell, too, and shot sparks like fireworks into the black sky.”

The great ship began the downward plunge that would take 1,518 souls to a watery grave.

Marshall fell asleep in a lifeboat of strangers and awoke to find daylight and towering icebergs all around him. “They looked more like ice islands.”

Marshall was one of the survivors who were picked up by the Carpathia, a Europe-bound liner with a capacity load of passengers.

Arriving at the rescue ship, Marshall recalled that children were hauled up in canvas bags. “The kids were all screaming, but I thought it was a pretty good ride until a sailor dumped me out on the deck.”

In all the frenzy, no one asked the child his name. That is why Marshall’s name was not on the list of survivors and the first book published in 1912 on the Titanic disaster listed Marshall Drew as going down with the ship.

It was impossible to get an accurate list of survivors. Marshall remembered waiting with a group of people in New York. To amuse himself, the child was handed a paper and pencil. His drawing? A great ship steaming on a sea rough with high waves.

“I remember a photographer took a picture of it so I ended up in the newspaper,” Marshall said.

He also was reunited with his tearful family who weren’t sure what they were going to find.

Life after Titanic tragedy

Marshall grew up, settled down in Waverly, Rhode Island, and tried to put the past behind him. He became a teacher and a talented painter. He married and had one daughter. But he always felt an icy chill go down his spine whenever April came around, he said.

With the popularity of the Titanic attraction and its sister museum in Branson, Missouri, I wondered what Marshall would have thought about the continuing interest in the tragedy that happened more than a century ago.

Probably, he would have responded the way he often did — with a shrug, a good-natured chuckle and a reminder that life is too short no matter how long we live. Marshall Drew died of cardiac arrest on June 6, 1986, at age 82.

“I could easily have died before I really lived,” he used to say. “Let that be a lesson to you – enjoy each day that you have.”

For more information: Call the Titanic Museum at 800- 381-7670 or visit www.titanicpigeonforge.com

Titanic Photo Cutlines

Photos by Jackie Sheckler Finch

The Titanic Museum opened in Pigeon Forge in 2010.

Museum guides are clad in Titanic-era attire.

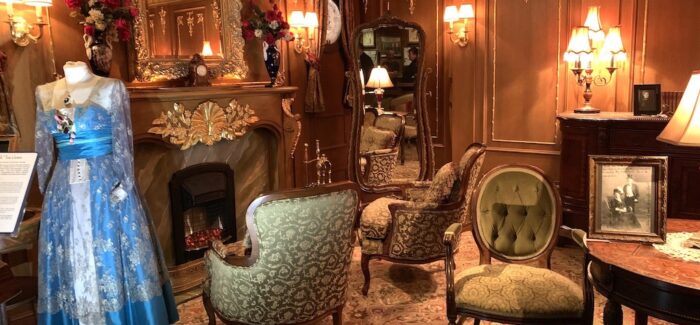

The recreated Titanic stateroom of Isidor and Ida Straus at the museum honors the couple who went down with the ship. Ida refused to board a lifeboat without her husband. (COVER)

Marshall Drew is listed on the wall of survivors at the Titanic Museum.

An exhibit on Titanic survivor Marshall Drew features a hat band the boy’s uncle had bought him aboard the ship. The band is possibly the only one in the world.

View Recent Comments